Every week on NPR you might hear pieces from StoryCorps. Nearly as often you might catch firsthand glimpses of history in "oral histories" without knowing what that term means. The Library of Congress connects some of these dots with an event on May 15 in its "Beyond the Book" series. The event marks the 75th anniversary of These Are Our Lives, a ground-breaking collection of life histories, what would today be called oral histories, produced by the government but intended to reflect the most individual elements of American life, from some of its most unsung citizens.

While researching my book on the Federal Writers’ Project, I learned of the nationwide effort to gather these histories (These Are Our Lives contains stories from the South but there are thousands more) from Ann Banks, author of First-Person America. Her book delivers more selections from that rich oral history material gathered by the Project, which she found gathering dust in the Library of Congress 40 years ago.

While researching my book on the Federal Writers’ Project, I learned of the nationwide effort to gather these histories (These Are Our Lives contains stories from the South but there are thousands more) from Ann Banks, author of First-Person America. Her book delivers more selections from that rich oral history material gathered by the Project, which she found gathering dust in the Library of Congress 40 years ago.

While researching my book on the Federal Writers’ Project, I learned of the nationwide effort to gather these histories (These Are Our Lives contains stories from the South but there are thousands more) from Ann Banks, author of First-Person America. Her book delivers more selections from that rich oral history material gathered by the Project, which she found gathering dust in the Library of Congress 40 years ago.

While researching my book on the Federal Writers’ Project, I learned of the nationwide effort to gather these histories (These Are Our Lives contains stories from the South but there are thousands more) from Ann Banks, author of First-Person America. Her book delivers more selections from that rich oral history material gathered by the Project, which she found gathering dust in the Library of Congress 40 years ago.Banks was suggested to me by one of the Project’s famous survivors, Studs Terkel, who championed oral history in many forms – from radio interview to his own books (which sometimes morphed into other forms like the musical Working) -- as a way to get history from real people.

In 1939 Terkel was working in the Project’s radio division, where he researched and wrote profiles for a weekly one-hour broadcast. He wasn’t doing oral history, as he admitted; his job was to write scripts about artists like Daumier, Van Gogh, Eakins, and George Bellows. But he absorbed the Project’s ethos of getting people’s stories to the public. Sometimes Terkel slipped out back with Nelson Algren, one of the life history interviewers, to a nearby bowling alley.

Sam Ross, who worked with Terkel in the radio division but also conducted life history interviews, summed up the atmosphere later: “Everybody felt alive,” Ross said. “We were linked to the community.”

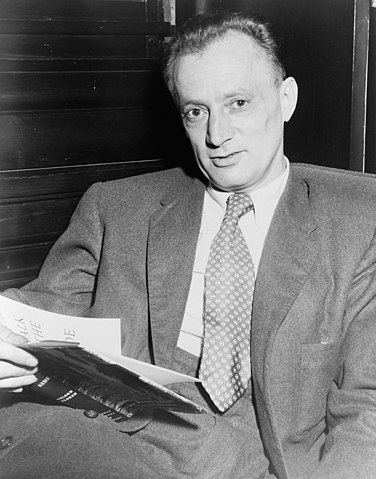

|

| Nelson Algren |

Through the life stories he gathered came a little-known picture of how segregation affected musicians. Despite the rules, styles crossed the color line and white musicians learned from African American musicians like Coleman Hawkins. “Hawkins was the guy,” Jacobson said. “Up till then nobody knew what to do with the sax in the orchestra.”

In the 1920s, jazz musicians had to abide racial segregation enforced by union rules. Some, like Spanier, learned by getting around those rules. Spanier started as a teenager on drums and switched to cornet, he told Ross, inspired by Joe "King" Oliver, who let a young Spanier sit in with his band. “That was unheard of in those days up North here, a white person playing with Negroes,” Spanier said. “I learned how to play from listening to Joe Oliver…”

In his Chicago interviews, Ross documented a firsthand history of jazz while it was still young, and felt lucky for the chance to hone his storytelling skills at the same time. He later wrote scripts in Hollywood. “I learned my dramatic craft there,” he told Banks for First-Person America.

Notes from a 1939 staff meeting of the Chicago’s folklore group give us a glimpse into how what we now call oral history was changing even then. Botkin had people like them gathering thousands of life histories across the country, and in his way was radically taking folklore out of the halls of academia. As Chicago folklore supervisor, Nelson Algren announced a new tack in collecting industrial folklore, saying that headquarters was planning a volume of urban stories along the lines of the just-published These Are Our Lives. Algren was excited by a new style of documenting urban stories that allowed for even more direct quotations, more direct expression of character from the people themselves. He held up a recent example that Ross read aloud. The examples “reveal a new way of writing,” Algren said, “which we'll attempt here.”

They debated the role of the interviewer, and whether the aim should be a narrative that readers find engaging, or one driven by the interviewee, which might uncover a potentially “truer” and more surprising story than the interviewer could anticipate.

|

| Margaret Walker |

Margaret Walker agreed: “If they have [your] one thing in their mind,” she said, “they'll just go back to it and keep repeating it.” Walker, too, would later hone her storytelling based on what she learned there. The focus was taking contemporary folklore into modern storytelling, a long way from the traditional tall tale prized by academic folklorists of the time.

At the Library of Congress event on May 15, Banks and Virginia Millington from StoryCorps will help put these innovations in storytelling from 75 years ago in the context of stories we hear today. Please come join us. It's free!